by Lucia Kurekova

Roma minority is among the most populous and the most problematic in the East-Central European countries (CEE). In spite of various work activation attempts and welfare tightening efforts implemented by the CEE governments in the near past, Roma population has largely remained out of the labor force. This has been so in spite of buoyant labor markets and vast labor shortages which were troubling domestic and foreign-owned employers. Logically, in the situation of high labor demand caused both by successful and rampant economic growth as well as by high rates of out-migration of human capital from CEE to the UK and Ireland, one would expect improved possibilities of employment even for those alienated from the labor markets during the periods prior to the EU accession, such as Roma.

While Roma are certainly among the disadvantaged (largely due to their educational and skill levels) and discouraged (not looking for work) workers, hard data about the extent and the character of their joblessness are scarce. Quantitative information about Roma in CEE which would be comparable to the majority population is nearly non-existent. This is so largely due to the push for political correctedness among the EU and other international authorities on the Roma issue which has in turn illegitimized the inquiries on Roma ethnicity in survey questions. Equally scarce is the estimation of the possible impact of various policies and labor market developments on Roma social inclusion or exclusion.

To fill the gap in data about their Roma citizens and to understand better the forms and channels of Roma labor market exclusion, the Czech government together with the World Bank carried a unique research project in order to estimate how Roma fare in the Czech labor market and to determine labor market barriers in their complexity. The Czech Roma World Bank study in my view breaks down a number of stereotypes, re-iterates some of the hunches which have not yet been robustly empirically confirmed, offers a complex assessment of the problem and – most importantly - a series of rather provocative policy recommendations.

On the basis of comprehensive survey carried out in the marginalized localities and targeted at the Roma, the Report finds – perhaps unsurprisingly – that Roma living in marginalized communities in the Czech Republic continue to face severe and multiple forms of labor market exclusion. The empirical findings put forward nuanced evidence on the multifaceted nature of Roma labor market marginalization. Starting with pointing out that Roma situation surpasses the categories of employment versus unemployment and moves to the arena of discouragement (not searching for work), the survey confirms that Roma suffer from low educational attainment. Leaving aside the reasons for this outcome, it has been found that majority of the Roma lack even basic functional and numerical literacy which in effect makes them absolutely unsuitable for the knowledge-biased new employment opportunities emerging in the CEE economies. These facts are complemented by strong gender and generational aspects to Roma labor market exclusion. While a good share of Roma men are employed (mostly in precarious and casual jobs), this is hardly the case for Roma women. Most strikingly, the survey results have revealed a strong generational dimension of the problem – there is a mounting evidence of the worsening of educational attainment and a significant downward mobility among Roma raised during transition.

Drawing Roma into education and into employment – the goals that the governments in the region have been trying to follow – scores again as a clear first-hand solution to the problem: the level of educational attainment, acquired skills and previous on-the-job experience predict well the success of Roma on the Czech labor market. In the Czech case, literacy and numeracy skills increase the probability of employment by a factor of two. If we seem to know where the solutions lie, the question emerges why have the attempts seen only very limited success so far?

The World Bank suggests that the culprit should be sought in (lack of) the quality and targetedness of the policy interventions aimed at Roma. To be precise, the limitations stem from the fact that the policies and approaches aimed at employment activation and labor market inclusion have not been sufficiently aimed at Roma. The policies have failed to recognize multifaceted nature of their distance from the labor market (lack of skills, welfare trap, heavy indebtedness, mismatch between jobs and skills, other labor market barriers) and to individualize the employment services. Welfare adjustments and public works program have not proven effective in providing longer-term solutions and bringing Roma out of poverty trap into labor market. The World Bank calls for a more balanced policy activation approach based not only on the responsibilities of job seekers but also on enhanced performance of the Labor Offices which need to focus on client profiling, integration of services in order to address multiple disadvantages, more culturally sensitive provisions and the introduction of performance measurement and evaluation of public servants. The policy adjustments further call for an enlarged partnership with private and NGO sectors and the enhanced focus on the next generation of Roma youth.

The fact that the recommendations coincide both in timing and in content with the basic principles and interests of the EU structural funds allocation is very good news for the CEE governments.

Reference:

Czech Republic: Improving Employment Chances of the Roma. Report No. 46120 CZ, The World Bank. October 2008.

Dec 22, 2008

On Roma minority in East-Central Europe: From Political Correctedness to Balanced Employment Activation Approach

Dec 18, 2008

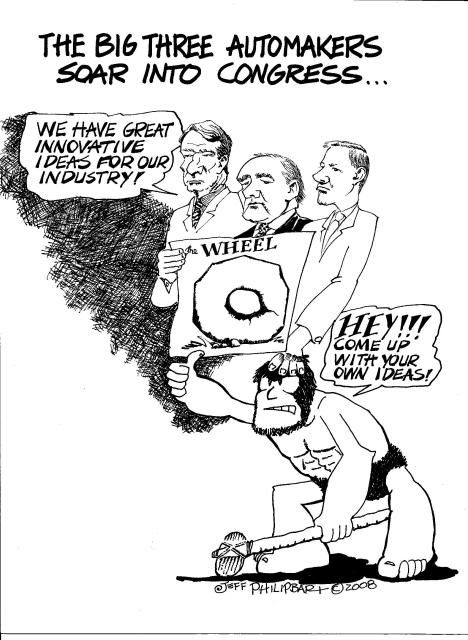

What does Varieties of Capitalism have to say about the bailout of the U.S. auto industry?

By Kristin Makszin

The different perspectives on whether or not to bailout the U.S. auto industry vary according to the alleged cause of the ‘crisis’ for the auto industry. Was this crisis caused by recent economic events (i.e. financial crisis, fall in consumption), bad decisions by the big three company leadership over time (producing SUVs, not fuel efficient automobiles), burdens of health and pension commitments to retired auto workers (a result of organized labor), political decisions, unstable oil prices, …?

Obviously there are multiple reasons why the auto companies are in the situation that they are currently in. But the problems in the U.S. auto industry are not new. Arguably, the current challenges are a continuation of a thirty year story – or perhaps an even longer one. The many events on this thirty year time line suggest that the U.S. auto industry is fragile. Which raises the question: can it be saved? And what would it take to save it?

Analysis of the current situation of the U.S. auto industry emphasizes the importance of the political and economic institutions that form the context in which businesses are embedded. Auto production began to move away from Detroit (to other countries and even other parts of the USA)—many argue—because of the high level of organization of auto workers in Detroit. But the decline of the auto industry in Detroit was also assisted by shifts in the global economy that allowed car production to increase in other parts of the world (the U.S.A. lost its comparative advantage in car production). Further the big three auto producers (GM, Chrysler, Ford) fell behind in the newest and most important innovation: greener cars. The reason that the U.S. auto industries fell behind in the ‘greening’ process could be blamed on the decisions of company executives, the American consumer, U.S. foreign policy, … But it is clear that NOW is time for the auto industry to innovate and the big three are already behind. According to the Varieties of Capitalism (VoC) framework, the U.S. economy relies on complementarities between deregulated labor markets, innovative product markets, competitive relationships between firms, a financial system where firms raise money from equity markets, and an educational system promoting general skills. The auto industry seems to be the exception to the liberal market economy framework. The strength of labor is impossible to ignore, thanks to the United Auto Workers. It would be hard to describe anything that happened in Detroit in the last 30 years as a part of innovative product markets. The big three have formed a ‘cooperative’ relationship in begging for the bailout. From a Varieties of Capitalism perspective, it does not seem surprising that the U.S. auto industry could not survive without the complementary institutions. Now that the equity-based financing is not sufficient and the executives of the big three (and many others in Detroit) argue that government funding should be used to keep these business alive-- because they are "too big" to fail.

According to the Varieties of Capitalism (VoC) framework, the U.S. economy relies on complementarities between deregulated labor markets, innovative product markets, competitive relationships between firms, a financial system where firms raise money from equity markets, and an educational system promoting general skills. The auto industry seems to be the exception to the liberal market economy framework. The strength of labor is impossible to ignore, thanks to the United Auto Workers. It would be hard to describe anything that happened in Detroit in the last 30 years as a part of innovative product markets. The big three have formed a ‘cooperative’ relationship in begging for the bailout. From a Varieties of Capitalism perspective, it does not seem surprising that the U.S. auto industry could not survive without the complementary institutions. Now that the equity-based financing is not sufficient and the executives of the big three (and many others in Detroit) argue that government funding should be used to keep these business alive-- because they are "too big" to fail.

Some Republican Senators (among others) have suggested that part of the bail out should demand pay cuts from the United Auto Workers and that innovation should be forced towards a more environmentally friendly car. Interestingly, the Republican Senators are addressing two other dimensions of the auto industry that seem to be mismatched with the liberal market economy capitalism that is predominate in the USA. But, from the lens of the varieties of capitalism framework, it is clear that the bailout package (even with all potential additional stipulations) would be incapable of making the auto industry work in the absence of complementary institutions. So perhaps it is time for Schumpeterian ‘creative destruction’ in Detroit.

From the streets of Detroit, the need for a bailout for the auto industry is clear. Too many lives and companies depend on it. If the big three are allowed to go bankrupt, Detroit will suffer and there will likely be strong ripple effects. But it seems clear at this point, a short term bailout is not enough. Drastic changes will be needed if the auto industry will survive in Detroit. If the big three stand a chance, they must use the advantages of their (supposed) institutional context to be the leaders in innovation towards greener cars. But it might already be too late. The only thing that seems certain for Detroit is that everything will change. Either the big three automakers will face real reform or they will continue their slow descent until U.S. auto production is only a memory.

The effects of this for Detroit are clear. But what will this mean for automakers in Europe and Asia?

Nov 29, 2008

Nationalization of energy companies (Slovakia not Venezuela this time)

By Andrej Nosko

That Mr. Hugo Chavez, Venezuelan president, is not too 'fond' of foreign investors is no secret, but that he has a zealous follower in the fastest growing economy of the EU, Slovak Republic, is not that well known. Slovak Prime-minister, Robert Fico is recently gaining attention for his plans of restoring full state control, and ownership over (49% of) previously privatized assets as his way of winning (?) the price war against the partly state-owned gas supplier. The previous government of Mikulas Dzurinda (and Finance Minister Ivan Miklos), has succeeded in putting Slovakia on the global investor map, and provided solid basis for the current economic growth. In 2002, this government has also sold 49% 0f Slovak gas company, SPP - previously integrated (now legally unbundled) to the Slovak Gas Holding B.V., a consortium of Gaz de France and E.ON Ruhrgas. The remaining 51% of SPP's shares are held by the Slovak National Property Fund.

"You have nothing to do with it"

/2008-10-17-telefonat.jpg)

"And Miklos"

"And Dzurinda"

Prime minister Fico, who in line with his political philosophy, has vocally opposed any and all privatization, is now, at least verbally, trying to get hold of the previously privatized assets, and calls for limiting the scope of private entrepreneurship in the country. Be it in the health care, pension, or energy sector. In this post I focus on the case of gas company SPP (although the story of Transpetrol deserves some interest as well). The current Slovak government doesn't believe in markets, and especially not in those in energy sector, and would like to dictate prices, and conduct social welfare policy by digging into the private pockets of foreign investors. To the calls, that prices of gas are into large extent dictated by Russian Gazprom, and SPP has to reflect rising prices on the wolrd markets Fico remains silent. When asked why Fico's government does not negotiate better prices of gas for Slovakia, he only replies that they would be stupid to do so if there are foreign co-owners to cover the costs of subsidizing the prices as well. The above cartoon says it all.

There are following options signalled by Mr. Fico to his co-owners of energy sector companies:

- either the private companies succumb to the political decisions (sometimes conveyed via the energy regulator) to keep their prices artificially low, conduct investments as Fico's government wishes, or

- their assets will be nationalized (threats to, SPP, Enel (EN: subscription required) article in SK), or

- the government changes the law in such a way to get the company to do what they want, or

- they sell their share back to the government (at the price they bought it for 6 years ago)

"Independent" regulator as a means of social policy

The story is not new. Chairman Fico, has been opposing the privatization since it was on the agenda. This is not incongruent with his party line. Since his party SMER got into the government, Fico has been struggling to gain control over the 'monopolies,' and the economy as a whole. The 'independent' regulatory body URSO (Regulatory Office for Network Industries), cannot be any longer seen as independent. To illustrate this point, we can quote the chairman of the regulatory board Jozef Holjencik, and his reaction to the alleged using of the regulator to promote social policy: "simply, it was interest of the state to protect them [households and small companies]. We respect that." That the work of the Slovak regulator is under political pressure was recently pointed out also by Blahoslav Němeček from the Czech regulatory authority during a recent conference in Bratislava.

Fight against 'the bad, bad capitalists' as a political marketing

Fico, was using the anti-capitalist rhetoric of class struggle against the corporations to get elected, and has never approved of the privatization (although very much needed for financing of the economic reforms (he did not approve of those either)). The price war (leaving the question whether he actually means it or its just a strategy of political marketing) of the government and the foreign investors in SPP has had so far three phases:

- Verbal threats of nationalization (August 2008)

- Attempts to change the conditions of privatization contract via change of legislation

- Concurrent Buy-back offer and change of Business Code (November 2008)

Although the foreign investors have minority of shares, at the time of privatization, they were given managerial control over the company - an element that has been a thorn in Fico's side since then - he has attempted to change the business law in order to change the conditions of the privatization contract, since that hasn't work out; he has threatened to expropriate the company, or offered an unrealistic buy-back at previous price (TA3, Téma dňa, 17.10.2008, 19h55) and finally succeeded in changing of the law (TA3, Téma dňa 04.11.2008, 19h55). Previously, an application for price increases to the URSO was a decision of the management. Now the general assembly of all stakeholders has to vote on the decision - thus state (with its 51% of shares) can block such decision.

Mr. Fico's argumentation is quite surprising, according to him (Téma dňa, 17.10.2008, 19h55), companies should follow the political decision of the government, or sell their shares back to the state at the original value (of 2002). Nonetheless, when the reporter asked him how this operation would be financed, prime minister only replied that he, "cannot say how this would be done, since they would do it in a similar way as buying back of Transpetrol (from Yukos Finance), but he cannot share details, in order not to threaten the Transpetrol buy back operation."

It is also important to remind in this context, what will happen according to Russian media (article in Russian, article in Slovak), after Slovak government buys back shares of Transpetrol from Yukos. If the Russian media is better informed, they might be handed to Russia, I have observed this eventuality already at the end of the previous post.

Absolutely surprising is how prime minister Fico, suggests to the co-owners of SPP to cross-subsidize the sales of gas. Pointing out the fact that SPP group is generating profit, nonetheless, he is indirectly hinting that SPP should subsidize the prices for households from the income from the transit-generated profits. The logic of this might be surprising to those in the EU, that are well versed in the Energy legislation. Slovak prime minister, although aware of this, is trying to push SPP to figure out how to bypass the anti cross-subsidization legislation in order to lower the prices for households. In the context, when the chairman of the regulatory board of URSO Jozef Holjencik also thinks that unbundling doesn't solve anything and only leads to higher prices (sic!), this comes at no suprise.

Finally, when a journalist asked, why state doesn't use its dividends (from the 51% shares) to cover for the protection of households, and to conduct the social policy directly, Fico only responded: why should only state cover for the costs of the household subsidies, [...] and if there is a 49% foreign shareholder, [...] they [state] are not stupid to cover it. (sic!)

Read more on Nationalization of energy companies (Slovakia not Venezuela this time)

Nov 21, 2008

Nov 17, 2008

G20 on banking regulation and leadership responsibility of EU

By Zdenek Kudrna

The G20 meeting this weekend was more important for the fact that major emerging economies were invited than for the substantive decisions. It all makes sense to get India and China at the same table with G8, but it does not make it easier for the US to swallow any kind of supranational financial regulation. I guess we need to wait for the new brand of Obama multilateralism to see any progress on this front.

The G20 statement is thick on good intentions, but thin on specific proposals: Increased transparency of financial sector, regulation of rating agencies, avoiding pro-cyclical regulation, increased information sharing between national authorities, expanding the FSF to include emerging economies and ensuring that IMF and other multilateral institutions to have sufficient resources to support emerging economies capital needs. It practically shifts the ball to the Financial Stability Forum that should develop substantive proposals for the next meeting of G20 in April 2009.

I doubt that FSF would be able to cut through the complexity of the global financial markets and formulate the future vision of the global financial architecture that could deal with all aspects listed by G20. Actually, I believe the EU 27 should be the leader in terms of substance of the new financial regulations. If EU cannot make progress towards supranational regulatory regime, than chances for global progress are slim.

Today EU is composed of both developed (EU15 + 2) and emerging economies (EU10) and its financial sectors cover the full spectrum from cutting edge of finance in the City of London, to rather sleepy backwaters in Prague or Bratislava (Today the 'advantage of backwardness' is worth billions of dollars as it means little exposure to 'innovative' financial products that proved 'toxic'. So Czech and Slovaks may still hope to get through the financial crisis without involvement of state finance). At the same time, EU financial markets are highly integrated, but the regulation is still based on home-country supervisors and its supranational dimension did not progress beyond vague memoranda of understanding and more or less informal consultation process.

EU is well aware of the discrepancy between the financial integration and fragmented regulation. A few years ago it even devised the so-called Lamfalussy procedure to be able to catch up on the regulatory side. However, even before the financial crises the regulatory integration hit the wall. Even the idea of regulatory colleges for major internationally active banks that now seems a nobrainer proved too politically contested to be passed.

As is often the case, lack of compromise boils down to interest-group politics. The political cleavages among vested interests in different countries proved too numerous. Brits, like Americans on the global scale, are suspicious of the supranational regulators. French push for centralized heavy-handed approach. Germans worry about their parastatal landes banks. The EU10 countries are not quite sure whether they should try somehow to adjust their regulatory regimes to the fact that all their banks are controlled from abroad (so they just hope for the best now). Moreover, the non-euro countries are not keen on letting ECB (which usurped the bank supervision responsibilities) to supervise their banks. Moreover, the retail banks are not keen on reducing regulatory barriers to competition, whereas wholesale banks support it. Moreover, parties on each side of these plentiful cleavages are shifting all the time. No wonder EU did not make much progress.

the other hand, times of crisis force some clarity of thinking and make clearer the relative costs and benefits of various arrangements. Some refined objections to supranational regime lose their persuasiveness as bad news keeps coming. Some political compromises (such as principles for agreements on burden-sharing of fiscal cost of bailout of banks active in many EU countries) that would be unthinkable in the normal times may be possible in extraordinary times. Economists call this benefit of crisis. If EU could seize on it, the rest of the globe would be more likely to follow.

Hungarian promises to IMF and future trends in EU10 banking regulation

By Zdenek Kudrna

Hungary had signed a Stand-by agreement with IMF on November 4, 2008. Apart the standard clauses on the fiscal and monetary policy, it includes a section on the financial sector policies. Although, these commitments are made under pressure to fence off the impact of the global financial crisis, they may foreshadow future changes of the EU10 banking regulatory regimes.

The reason why Hungary is threatened by the financial crisis more than her Visegrad neighbors is fiscal profligacy of her government. High debts and high deficits of public finance over the last few years induced the independent central banks to restrictive monetary policy. In turn, high interest rates (and rather stable exchange rate of forint) motivated households to borrow in euro, Swiss francs or even yen. This resulted in the much higher vulnerability of household balance sheets as they essentially bear unhedged exchange rate risk. Both of these risks were exacerbated by the financial crisis that triggered liquidity trap and capital outflows from emerging markets.

In this context, the Stand-by agreement reviews what by today counts as standard firefighting measures including:

To address the foreign lending problem of households, the agreement envisages that banks and indebted families would

The crisis also induced the Hungarian government to submit laws to the parliament that would allow Hungarian Financial Service Authority and financial infrastructure to catch up with what most of their EU10 neighbors have done a few years ago.

Judging what all this means for the future of banking regulation in EU10 is fraught with uncertainties. However, unless we see major moves on the EU level and providing that existing regulatory regime will only be patched not scrapped, we could observe the following:

All of this has always been on the table. However, the unpleasant experience of Hungary and also Baltic states, Romania, and Bulgaria, may help to turn proposals into action in other EU states and on the EU level.

Nov 15, 2008

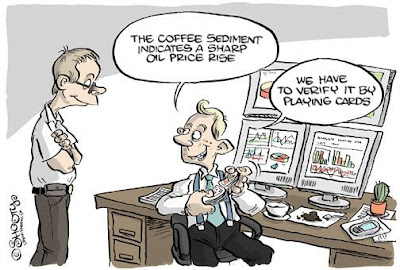

Crude’s Bumpy Ride: In Search of Fundamental Determinants of Oil Price

By Michal Trnik, PERG guest author, http://michal.trnik.sk/

Providing credible and accurate forecasts of crude oil prices was always a tricky business resembling rather fortune telling than an exact science. With the unfolding oil price volatility, the reputation of analysts suffered a heavy blow once again. Only recently, many experts prognosticated record high $200 per barrel to be hit in a reasonably short time. Today, oil price continues its unexpected nose-dive, and oscillates below $60 a barrel, however. Source: Shooty; used and modified with the kind permission from the author.

Source: Shooty; used and modified with the kind permission from the author.

To be clear, explanations and estimates of crude prices were always a messy field. The recent unexpected price volatility unraveled weaknesses of many silver bullet explanations and left average consumers with the pressing question on their mind: "So who the hell can I blame?" The list of potential culprits has always been long.

It’s OPEC, stupid

The OPEC’s influence is still by many believed to be one of the most important causes defining the crude oil price. However, the market power of OPEC today is not what it used to be. Although the shortening of supply to increase oil price was used as a tool to boost producers’ profit, nowadays the situation is largely different as a result of OPEC being an example of undisciplined cartel; increasing availability of energy substitutes, and the nature of the current oil pricing system. The so called reference price regime in place today is based on two main freely traded reference crudes – Brent and WTI – both of which determine the price of other types of crudes, which are not freely traded. This current regime thus largely eliminates the drawbacks of the OPEC price regime (1970-85) in which prices were unilaterally determined by producers.

Crises raise prices

Political crises and instability in oil-producing regions became one of the most routine media used explanations on oil price increases. Such interpretation, however, is of no use given that political unsteadiness is rather a norm than an exception and in today’s globalized world it is fairly easy to find a geopolitical disturbance to which climbing prices can be attributed. No doubt that severe geopolitical crises can impact oil prices. Nevertheless, this explanation has to be used reasonably and with extreme caution.

Running out of oil (once again)

The Hubbert’s famous peak-oil theory rightly predicts that oil as a definite source will have to reach its production peak sooner or later. The price is expected to rise as a consequence of oil production reaching its terminal decline and thus becoming increasingly scarcer. There are many "prophets" who regularly omen that the end is near or had mistakenly announced the peak already some decades ago (video at 5:45). Briefly, we’re not there yet. Linking any oil price run-up with the alleged peak thus cannot be taken seriously.

Hedge funds, pension funds, speculators and other vermin

Various funds and fortune hunters are often accused of sky-rocketing oil prices and such view still enjoys credibility whether among consumers, politicians, analysts, industry executives, or among former chief speculators themselves.

Keeping the argument as simple as it gets, it was very recently the speculators were accused of artificial inflating of oil price, which was believed to be above the level at which demand is in balance with supply. Higher price allegedly created by artificial speculative demand would in effect mean a necessary existence of physical excess oil supply that has to be hoarded by the seller for future sale to fulfill his commitments to the buyer. Likewise, if the price is suddenly too high, then demand from the traditional consumers would shrink, leading to a large surplus of the oil in the market. The question is: what happens to this excess supply then? Well, as it is not consumed it should be stored in physical inventories somewhere. There is no empirical evidence of such accumulation at any point during the last price increase, however, which in turn means that the alleged existence of price bubble does not hold up to the economic reality.

Moreover, speculators cannot directly influence prices as they are nothing more than price bettors willing to throw their millions into the market hoping their forecasts of future price will be accurate enough to earn them profits. In any case, the oil price remains unaffected as betting on the future oil price has no direct effect on actual price moves similarly as betting on horses has no direct effect on the winner of the race no matter how much cash and how many people bet on that particular horse. It is the futures market which is the main playing field of all ‘speculators’ who instead of buying physical barrels bet on future prices of oil by buying futures contract.

What the future(s) hold

Sometimes the least sexy explanations are the most valuable ones. The futures market and trading of futures is the key to understanding the working of current oil price mechanism. The market with futures, which is a market for financial contracts, is where the oil price is determined.

The oil market, like any other commodity markets, can be divided into the spot market and futures market. In the spot market physical “wet barrels” of oil are traded. The futures market, where “paper barrels” are traded, on the other hand serves the needs of those who need oil in the future but do not want to purchase it today but rather when their actual demand arises. These traders instead of purchasing physical oil barrels opt for a futures contract which entitles them for those barrels later on. The price of such contract is set by an agreement between the buyer and seller. At the same time these contracts make predictions about the future direction of prices, which determines also the current price on the stock market. Today, only a small portion of oil is traded on the spot market, however, as it has became very thin due to its insufficient liquidity caused by a rapid decline in oil production of the two reference crudes (WTI and Brent). The futures market should not be understood as a cause of the oil price changes but rather as a place where it happens.

Current volatility and good ol’ supply and demand

In economics you won’t usually go off the track too much if you go for the supply and demand explanation whenever you are not sure about the answer. There is nothing fundamentally wrong with such answer neither in the oil markets. As the world tends to be complicated, saying supply and demand is not enough, nevertheless it is crucial for understanding the recent oil price tumble. Moreover, the recent unexpected plunge of oil price indirectly confirms that OPEC, political crises, peak oil or speculators are not the most important factors shaping the oil price.

One barrel of fresh crude without bubbles please

The recent extreme volatility is related to shocks to both supply and demand. First, the sharply increasing demand for crude in developed and developing countries combined with structurally stagnant supply stemming from persistent shortage of refining capacity stood behind the soaring price. Second, its subsequent plummet is a logical reaction to contracting demand caused by slumping economies all around the globe triggered by the credit crunch.

Supply and demand, no rocket science. Making analogies between the development of price in oil markets and the price bubble we’we encountered in the US housing market thus seems rather inadequate.

Nov 5, 2008

The Current Financial Crisis: Causes, Consequences and Lessons for Theory and Policy

POLITICAL ECONOMY RESEARCH GROUP organized a round table discussion on:

THE CURRENT FINANCIAL CRISIS: CAUSES, CONSEQUENCES AND LESSONS FOR THEORY AND POLICY

Pictures and complete audio recording (also for download as mp3), and full written summary, from the event available bellow .

Event took place on Tuesday, November 4th at 5.30 p.m. at Central European University Budapest, Nador ut. 9 (MB 201)

Discussion was chaired by Julius Horvath (IRES/ECON), with following participants: Laszlo Csaba (IRES), Bob Hancke (POLSCI/IRES and LSE), Don Kalb (SOC.AN), Ugo Pagano (ECON), Gyorgy Szapary (ECON)

Audio Recordings provided by Gergo Medve-Balint:

1. Gyorgy Szapary Download mp3

2. Bob Hancke Download mp3

4. Ugo Pagano Download mp3

5. Don Kalb download mp3

6. Laszlo Csaba download mp3 A download mp3 B

Discussion:

Part 1: download mp3

Part 2: download mp3

Part 3: download mp3

Part 4: download mp3

|

| Financial Crisis Panel - PERG - CEU, 4 November 2008 |

Summary: By Vera Asenova

The Current Financial Crisis: Causes, Consequences and Lessons for Theory and Policy

The good news for academics these days is that in time of financial crisis explanations for what the hell happened, are in high demand. The supply of analysis of the situation is not scarce either. Suddenly, all schools of thought celebrate the ultimate prove of their point, the crisis finally demonstrating empirically what the theory has been developing for so many years. Yet none of them is admitting defeat, and none will really disappear.

In an attempt to generate an inclusive debate across disciplines, theories and viewpoints PERG organized a public round table discussion under the title: The current financial crisis – causes, consequences and lessons for theory and policy. Our guest speakers were CEU faculty members from different departments: Laszlo Csaba (IRES), Bob Hancke (POLSCI/IRES and LSE), Don Kalb (SOC.AN), Ugo Pagano (ECON), Gyorgy Szapary (ECON), the discussion was chaired by Julius Horvath (IRES/ECON).

Prof. Szapary, who is also a vice-governor of the National Bank of Hungary, started with outlining the main reasons for the subprime crisis - excess liquidity, and low interest rates, which were kept for too long of a period in the USA, while inflation was also low; on the housing market the high loan to value ratio generated a big amount of toxic assets in the banking system, which is the second main reason for the crisis. He presented the bubble as a rise of real estate prices much higher than the rise of production costs for homes and the population growth. This bubble soon triggered panic: “social intoxication,” and confidence crisis, with banks having stopped lending to each other. The lack of regulation on investment banks and hedge funds had put them in a position of being “too big to fail”, which was not recognized by the national authorities on time. What followed were bankruptcies unseen before in the USA, UK, and Europe, which called for decisive government action. They had “nothing right on the left and nothing left on the right” to use Szapary’s words. Still, two kinds of policy actions followed – central bank injection of liquidity into the financial system, and government bailouts of banks through recapitalization of banks, purchases of toxic assets and deposit guarantees. 3000 billion USD is the total US government commitment so far. Growing fiscal deficit and government debt, followed by increase of taxes, unemployment, inflation and huge losses of wealth are the main consequences of the crisis. One of the lessons to learn is that measures for international burden sharing are needed in a globalized financial world. The countries with the majority of foreign owned banks face a problem of mother banks terminating lending to their subsidiaries abroad, thus forcing the national central banks to bail them out, or inject liquidity beyond its capacity. At the same time, an obvious conflict of interests arises for the central banks in the countries of the origin of the mother banks, who feel reluctant to export capital to foreign financial systems. Who should be the lender of last resort in a globalized financial system?

Bob Hancke spoke of the political roots of the crisis, which in his view lies in the independence of central banks. Lack of regulation, the political roots of the crisis lie in the decision taken in the nineties to deregulate the financial sector. Central Banks have failed as apolitical regulatory agencies, and many of them have in fact been captured by investment banks – serving their particular interests by keeping the interest rates too low. The rule based monetary policy worked for a short while, but soon governments had to come back into the driving seat, although formerly they were considered incapable. Today’s crisis proves this is not true; governments are the viable alternative to failing markets. What they are doing today is not so different from what they did in the thirties. After ”trying out” communism and fascism as alternatives to laissez-faire, social democracy emerged as an understanding that markets are fundamentally good, but you need to regulate them well. It is the kind of viable system where governments play a large role in the economy through central banks and fiscal policy. Hancke opened the debate on central banks and what they are really for. Currently their mandate is diffuse, focused on price stability without achieving it, while the stability of the financial system is taken out of the mandate. Thus the current crisis has shown that central banks are losing their legitimacy, as well as their independence.

Ugo Pagano’s talk entitled “The End of Anglo-American capitalism?“

Both models of capitalism are susceptible to systemic crisis – the one based on flexible financial and labor markets, and the one based on arms length relations between creditors and debtors. The weakness of the Anglo-American flexibility model have now become very clear, and they come down to diluting of agency relations, and destruction of social capital; lower total monitoring; and arising of new rigidities. This new rigidity plays itself out as an impossibility to renegotiate the debt when the price of the collateral went down – when everybody is a creditor the bargaining and renegotiating of debt becomes very difficult.

Secondly, Pagano also shares the view that bubbles are characteristic of the economy – high expectations drive prices up, this was the case of the internet bubble, oil bubble etc. each bubble has a grain of truth – a reason to believe that prices will go up (internet is a great thing; emerging industries, China and India will increase global oil demand etc.) but this grain of truth gets hugely inflated. The more financial instruments created on the basis of this inflated expectation the bigger the bubble gets.

A third phenomenon is the moral hazard problem – some actors are too big, and too interconnected to fail. The danger would have been less severe if these institutions were never allowed to become so big, or to have kept the financial sector under control.

What will happen now? America and Europe follow two different roads. America is an earlier democracy, which believed that wealth should not be concentrated in the hands of a few big families but dispersed. Still the financial sector performed a hidden redistribution function, and is currently in crisis.

Europe’s trajectory starts with first having the big families ruling through concentration of capital. On the other hand, the power of workers is concentrated in trade unions that react, and trigger change.

England started as a strong families, and strong unions capitalism, and moved to a dispersed ownership American model, and is now in crisis due to its huge financial sector and huge state intervention. But this is not the end of the Anglo-American model of capitalism.

Don Kalb – the VoC [Variety of Capitalism] schools is happy about this crisis as it puts the question of what kind of regulation are we going to have. But we need to discuss societies, because societies drive politics, which drive institutions. One thing we learn from this crisis is that institutions don’t work if they are left alone. Even if you introduce more regulation, you need societies to do politics. To analyze the real social forms beyond the Polanyian and VoC framework. Kalb proposed a society-based explanation of the crisis. The neoliberal policies dominant in the last thirty years had two crucial characteristics, which are deeply contradictory and colliding:

- Increased ‘financialization’ of social life – social relations, markets, states;

- Increased social inequality and polarization.

These coinciding developments can explain why the subprime private sector is the domain of the crisis. Regulatory interventions try to prevent, or react to the problem, but cannot succeed. The neoliberal era is an era not of deregulation but of private regulation of risk; the crisis starts form large private indebtedness in the core, which built up in the nineties, and burst out recently. Income stagnation was combined with injections of cheap liquidity (provided by China, Japan and Germany) prevented the contradiction from colliding. Growing private indebtedness, declining prices and inflexible relations have been the causes of the crisis. The possibilities of reversing this adverse combination of social polarization and ‘financialization’ of society lies in the future political decisions taken in the USA. Hopefully Obama, who gets elected today, will listen better than his predecessors.

Laszlo Csaba “The Hungarian reaction. A reaction to what?” Csaba focused on the situation in Hungary which is not facing a deep capitalist crisis like the USA but a panic on the financial market. Due to the underdevelopment of its financial system, Hungary can never commit the mistakes of the USA – the benefits of backwardness. Before discussing the Hungarian government reaction, one needs first to define a reaction what is being sought. Unlike the great depression 1929-35 an overall contraction of GDP in the American economy is not present om the real economy which is not in recession yet. Situations of panic are typical of the financial market. This market has been the source of immense wealth creation – the system which is unregulated, unjust etc. has contributed to eighty percent of the wealth in the last hundred years.

The name of the game is psychology, and the main issue here is the trust. In Hungary the government has very low credibility both because of its members, and because of its economic policy. People do not care about the government because it is politically compromised, and also because it keeps making welfare promises it does not deliver. Low level of credibility is an especially big problem in times of crisis.

Now the reaction of the government was not to listen to the warnings. The national bank, research institutions, and other organizations have been warning the government that tax and spending policy does not work in a small open economy, which has high degree of vulnerability. In this case sustaining a national currency is a luxury and it also enhances the vulnerability of the economy. Joining the currency union as soon as possible should be a priority also of the government, as well as of the median voter. When the crisis hit, the government did not believe it, and kept saying that this was an American problem, which does not affect Hungary. In addition to the liquidity crisis, there was a recent attack on the Hungarian Forint, which lead to almost 20% devaluation of the exchange rate, and from this moment the panic spread. The forecasts was a slum of - 1.5%. An emergency plan was provided by an IMF standby loan of 25 billion dollars together with the European Union, and the World Bank. The attack has now been partially reversed, and the stock exchange is recovering.

Csaba was skeptical regarding the benefits of crisis often discussed by economists – the idea that hard times provide a window of opportunity to sell the wonderful ideas of the economic science to politicians, and bring reform. The primacy of politics will close the window of opportunity and instead of long term economic growth, short term measures, and muddling through will take place for as long as possible.

What followed was an exciting discussion, which can be found on our blog. A commitment to organize another discussion on the topic later, and a few rounds of drinks at a nearby bar.

Read more on The Current Financial Crisis: Causes, Consequences and Lessons for Theory and Policy

Nov 3, 2008

George Soros' lecture at CEU

Public Lecture by George Soros, Founder of CEU and Honorary Chairman of its Board of Trustees

Comments on the Global Financial Crisis

Date: Tuesday, November 11, 2008

Time: 6:15 p.m. - 7:45 p.m.

Location: CEU Auditorium

Dear CEU Community Members

We are privileged to announce a Public Lecture by George Soros, Founder of CEU and Honorary Chairman of its Board of Trustees

Comments on the Global Financial Crisis

Chair: Lajos Bokros, COO/Professor, Department of Public Policy/

Department of Economics

Date: Tuesday, November 11, 2008

Time: 6:15 p.m. - 7:45 p.m.

Location: CEU Auditorium

George Soros is not only a legendary financier and philanthropist, but also a widely-read author. His latest book, The New Paradigm for Financial Markets: The Credit Crisis of 2008 and What It Means was released in April 2008.

The opening sentence, summarizing his sense of urgency about the turmoil in the financial world, “We are in the midst of the worst financial crisis since the 1930s.” has of course proved to be an accurate prophecy. As the subsequent global financial crisis has unfolded, he has been asked to speak and write on this topic in the leading financial and news publications and television worldwide.

As there will be an enormous amount of interest in this lecture we are restricting it to the extended CEU community for this reason. We also ask you to indicate whether you will be attending by Monday, November 10, at noon. Seats cannot be reserved, except for one group of students originally included in program, and will be on a first come-first served basis. Your response regarding your attendance will give us an indication of numbers and thus assist us in arranging additional seating, including a screening area.

Please RSVP to soroslecture@ceu.hu by November 10 at 12 noon.

For your reference we have some background reading materials before the lecture. These are available on www.ceu.hu/soroslecture

Your

Yehuda Elkana

Nov 1, 2008

'Return Ticket to Dublin Please'

by Colm Kelly, Ireland (PERG blog guest author)

From my experiences working in two major Financial Institutions, which are primarily involved in the funds industry, I have noticed a rapidly growing number of vacancies are being filled by Central European Immigrants. The majority of whom come from Poland with the remainder hailing from countries like Hungary, Lithuania, Slovakia and the Czech Republic. From my view point there are three main factors in the influx of CEE workers:

Firstly, financial companies based in Ireland are made up largely of American and Japanese firms which enter the European markets at the place of least barriers. Ireland provided least barriers to entry approx. 15 years ago through substantial tax breaks/incentives and a highly educated and young workforce. This highly educated workforce is now also highly paid and such companies now seek other opportunities to minimise costs and first on the list is to relocate. Relocate where though? China? Too far removed from their market place. Australasia? Already possesses a fully developed financial services industry and wages will provide a huge problem. So what about Central Europe? Relatively low wages. Good infrastructure. Close to the target market and also possesses a very highly skilled and educated workforce. So what is the best way to kick-start the transition? Attract the target CEE workforce to your current location, allowing them to receive the perfect on the job training while preparing the company for a move to CEE.

This leads to the method of attraction, the second reason. My current employers, the global market leader, selected a target demographic and advertised heavily in local and national newspapers and also targeted university graduates. By offering good wages and helping with accommodation costs they attracted a large group of Polish recruits which were brought over to the Irish office and settled into the working environment with ease, largely due to their excellent grasp on the English language and because of their strong work ethic.

What lead to their easy integration into the Irish workforce was the third reason. The governments ’open door’ policy allowed the importation of EU8 workers without any restrictions or limitations. It was quite literally a ’help yourselves’ policy. Whereas other immigrants, Nigerians for example, had to apply for visa’s and re-entry visa’s anytime they’d like to return home for a holiday, the CEE workforce were free to come and go as they pleased without restriction.

Other factors which helped promote the influx include, word of mouth, a 100,000 strong Polish community which has fully integrated into Irish everyday life and the opportunity for CEE immigrants to enjoy a high standard of living with many opportunities to discover other European cities through quick and easy local airlines. As more and more Polish workers arrived and integrated into Irish life, word would spread back home and would also filter through other countries such as Lithuania. About 3 years after the initial influx of Polish workers, other nationalities started arriving in greater numbers. I now work in a newly acquired company which is made up of 50% CEE workers, all hailing in equal numbers from all of the above named countries. From many conversations with these workers, they all have common reasons for migrating to Ireland. The opportunity to earn a higher wage and save enough to return to their home countries with a sufficient nest-egg. The lifestyle played a major part in their choice of destination with a solid CEE base community now living and working in Dublin, many immigrants find it easy to settle into life over here.

So what does this mean for us Irish? Well in the eyes of our employers we have now become a highly educated but also highly overpaid workforce. While I have seen no restriction in the progression of immigrants up the corporate ladder, most have not been here long enough to have climbed very far so now is the ideal time for these foreign companies to relocate as wage ‘cut backs‘ in high positions are now possible. By chance, my company just happened to be building a new European base in Poland over the last 3 years which has just recently opened and a large portion of the Irish based work and Polish workforce have been redeployed to Krakow. The global recession has also timed itself perfectly to allow such a company to justify the move to its Irish hosts, who are among the worst hit by the credit crisis and housing market collapse. This is routine business strategy for a global player though and it was our turn to play our part as grateful hosts for ten or so years and to now accept our fate. Now I believe CEE states will play the very same role as we did and hopefully they will last longer than we did.

Nine “Truths” about Central European Migrants or "Who they are and how they fare?"

by Lucia Kurekova

Not much attention has been given to unraveling the backgrounds of the EU8 migrants in Britain and Ireland, the two countries which attracted the most labor from the new accession states. While the magnitude of flows from EU8 and the disputes about the impact of these flows on the labor markets of host countries has generated much new research, the investigations remain to work with aggregate categories. This in essence means that most of the knowledge we have about who the Central European migrants are and how they fare at the labor markets exists in the aggregate form for all EU8 countries together. Hence, while we cannot really establish whether or how are the Czech migrants different from the Slovak migrants, here is what we know about them as a group from the transition economies so far:

1. A great majority of all EU8 migrants are between the age of 18 and 35.

2. Male migrants slightly prevail over female migrants.

3. Nearly two thirds of migrants, when registering, claim that they do not intend to stay (in the UK) longer than 3 months.

4. Most frequent sectors of employment for EU8 migrants (in the UK economy) are: administration; hospitality and catering; agriculture; manufacturing; and food/fish/meat processing.

5. EU8 migrants earn the least relative to other migrant groups (in the UK).

6. EU8 migrants are on average the most educated relative to other migrant groups (in the UK).

7. EU8 migrants have not been entering the host country economy in order to succumb to the welfare system.

8. The social and wage mobility of EU8 migrants seems to be so far very low.

9. The success of EU8 migrants is strongly defined by the knowledge of English language.

If you come from any of the EU8 countries or happen to be living in one of the host countries, these facts are perhaps not much of a surprise to you (if they are, please let me know). Nevertheless, all together - as they are and if we are to believe them - they seem to point to a number of failures. Among other things, they raise a series of questions about the quality of education in ex-transition economies, about the ability of home governments and markets to provide opportunities which would allow freshly educated teachers to teach in Presov (eastern Slovakia) rather than serve beer in Cardiff as well as about the ability of host governments and markets to use ‘well’ the human capital they have at hand. Still, the story is clearly more complicated and definitely more interesting once we look behind the dry numbers and facts. For that I recommend the post of my guest writer, Colm Kelly from Ireland.

Data based on:

Accession Monitoring Report. May 2004 – June 2008. A Joint Online Report by the Home Office, Department for Work and Pensions, HM Revenue & Customs and Communities and Local Government, June 2008.

Pollard, Naomi, Maria Latorre and Dhananjayan Sriskandarajah. “Floodgates or turnstiles? Post-enlargement migration flows to (and from) the UK.” Institute for Public Policy Research. April 2008.

Drinkwater, Stephen, John Eade and Michal Garapich. “Earnings nad Migration Strategies of Polish and Other Post-Enlargement Migrants to the UK”. Paper prepared for the presentation at the European Ecnomics and Finance Society Annual Conference, Sofia, May 31 – June 3, 2007.

Oct 30, 2008

3rd Energy Forum Budapest

The event opened by a presentation of The annual Energy Outlook 2008, introduced by Justine Barde, EIA Economist. Second day was opened by President Solyom, followed by 7 panels on wide-ranging topics. Out of the political speeches, Hungarian opposition leader Viktor Orban, in his address, emphasized new regional cooperation, strengthening north-south infrastructural linkages, and framing of the energy crisis as an economic opportunity. It was quite interesting hearing from him also about the geothermal and solar opportunities in Hungary, which was later on taken up by more technical presentation by MOL experts (MOL is a leader in Geothermal in Hungary). Zeyno Baran emphasized the need for clear Russian strategy, for EU and especially for CEE. Kresimir Cosic, member of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the Croatian Parliament, presented Croatian Energy strategy and plans to build LNG terminal at Krk. Interesting discussion emerged during the panel on trade-off between competition and Energy security, when Laslo Varro, vice president for strategy and development of MOL Hungary, and Said Nachet, the energy director of International Energy forum secretariat, Saudi Arabia discussed market issues of spare capacity, pricing incentives of not removing the infrastructure bottle necks, and the effects of (de)regulation and unbundling.

Although there were no surprising news, if one follows the energy landscape in Central Europe, the discussions pointed out some re-emerging topics, and highlighted issues that will be on the agenda in the upcoming months or even years. We will surely follow developments around Nabucco v. South Stream, which should be discussed early next year at the special Nabucco summit to be held in Budapest, as well as issues of Central European Energy cooperation, which does not yet have any specific contours. Read more on 3rd Energy Forum Budapest

Sep 12, 2008

The Economics of Energy Security panel

Freedom House Europe, with support from the embassies of the United States, the United Kingdom, the Czech Republic, the Netherlands, Norway, and Central European University, organized a roundtable series focusing on energy security in Europe.

PERG section editor Andrej Nosko moderated the first of the series, The Economics of Energy Security panel. The proceedings of the panel are now fully available in flash video format on the Freedom House Europe website. In addition, downloadable versions of select presentations are also available.

Video of Andrej Nosko introducing the Freedom House Panel on The Economics of Energy Security and the first speaker Professor Alan Riley from City University in London discussing the challenges posed by Russia’s inefficient gas industry to Europe’s long-term energy supplies:

More videos are available directly from the Freedom House Europe website.

Aug 28, 2008

Back to the Balkans. Volkswagen’s Relocation Plans and State-led Investment Promotion in Visegrad Countries.

By Michal Trnik, PERG guest author and MA IRES 2006 graduate

A recent news post concerning the alleged move of Volkswagen’s factory from Slovakia to Bosnia triumphantly lifted eyebrows of those who croaked the unstoppable and permanent eastward movement of foreign capital where the costs are irresistibly lower. According to these pessimistic prophets it was only a question of time when Central Europe cease to be interesting for foreign investors, which will result not only in its decreasing influx but also in direct relocations of multinationals’ production facilities.

The noticeable fuzz in Slovakia spurred by the announced VW’s plan to move whole production to Sarajevo was even magnified by citing no reasons for such a move. The ongoing silly season further boosted speculations on all fronts. Exorbitance of these catastrophic scenarios was refuted early on by Reuter’s refining follow-up, which confirmed only the relocation of small line that would have no direct impact on neither of VW’s two plants in Slovakia whether in terms of decreased production capacity or employment.

Panic is not justified. Not yet. Slovakia and other V4 countries in comparison to Bosnia still posses many FDI luring advantages. The decision of Europe’s biggest car manufacturer to start a new line of production in Bosnia rather than in Slovakia, however, sends a specific signal to Slovak government and other Central European countries as well. In particular, it serves as a good case for identifying persisting gaps in long-term investment promotion frameworks across the region.

Several speculative reasons why VW opted for Bosnia can be spelled out. Some argue that fundamental push factors that contributed to VW’s decision dwell in acute lack of skilled labor force, strengthening Slovak currency, sprawling anti-business rhetoric of current populist administration and end of tax holidays for the company. While others stress Bosnia’s pull factors such as incentives not subjected to strict EU limits, previous history of VW car production in Sarajevo and site’s potential to serve as testing grounds for further relocations.

Although none of the abovementioned reasons have to be directly responsible for the restart of VW’s production in the Balkans, they offer a larger picture concerning the state of current strategies to attract foreign investment in Slovakia and Central Europe. The Tatran Tiger’s economic success was largely generated by immense FDI inflows spurred by liberal reforms of Dzurinda’s governments. Most of investments came from at that time desired manufacturing industries, which helped to transform once economic laggard into the world’s biggest carmaker.

New challenges need fresh ideas. The V4 region soaked with manufacturing FDI demands new investment promotion approaches in order to move up the development ladder. Such strategy needs to be dynamic and has to reflect country’s development goals. In Slovakia, however, such scheme seems to be completely missing as can be seen on the country’s excessive and continuous reliance on automobile industry.

VW’s relocation to Bosnia certainly is not the first and will not be the last. Constantly rising wages in Slovakia and soaring world oil prices having detrimental effect on the car industry globally show obsolescence and fragility of country’s auto-industry focused investment promotion framework. Despite some indications of new winds blowing in minds of policymakers nothing like coherent, functioning and future-oriented investment promotion strategy was implemented. Although some minor diversification of FDI inflows into electronic industry occurred recently, Slovakia considerably lags behind in the amount of projects in high-tech, sophisticated services, IT or R&D. These require more brains than heavy machinery, can help transform the country into a modern service-based economy and make it less vulnerable to companies’ relocations. Slovakia’s close neighbors seemed to understand this some time ago.

The main regional leader in this respect is the Czech Republic, which continuously attracts sophisticated investments with high value added. The Hungarian investment strategy registered noticeable successes in form of highest FDI stock per capita in CEE and has a relatively better balanced structure as well. In fierce regional bidding wars for mega-investment projects, however, Hungary often does not hesitate to dig into taxpayers’ pockets in form of extra sweeteners offered to foreign investors. The case of Hankook Tire and speculations about Daimler’s recent investment are good examples of Hungarian generous aid to multinationals.

Daimler’s investment shows that V4 countries are still attractive for investors and can effectively compete with cheaper countries in the East even for large capital intensive investment projects. As Daimler is believed to be one of the last automobile investors in this region it is high time to rethink investment promotion strategy for those who did not do it yet. Czechs, Hungarians and even Poles did their homework on time and not only adjusted but also implemented their strategies oriented towards more perspective type of investments.

The age of massive capital and technology intensive manufacturing FDI inflows to the region is over. Forward looking investment promotion strategy is one of the necessary ingredients for further growth. Attracting investment in cutting edge technologies, services, R&D together with increased effectiveness of current production can become corner stone of its future economic success. Slovakia better learns this lesson quickly in order not to get caught unprepared face to face messages like that announced by VW.

August 28, 2008

Aug 27, 2008

Energy and the South Ossetian War: the BTC as the Main Casualty?

By Vladimír Šimoňák, PERG guest author

For the first time in the nearly twenty years since it began, the events in and around South Ossetia hit the world´s media landscape, almost overshadowing even the massive spectacle posed by the beginning Beijing Olympics. A peculiar tragedy of the events consists in the fact that this one has been regarded as the „friendliest frozen conflict“ in the South Caucasus. Intermarriage rates between Ossetians and Georgians and the density of contacts between ordinary citizens on both sides, the frequency and ease of travelling between the regions had been much higher than in Abkhazia and Nagorno Karabakh. Yet, few people ever assumed any degree of hostility between the two peoples might have caused the events of August 2008. It is equally evident that NATO´s interest in Georgia is to a major degree substantiated by the hydrocarbon transport routes running through the small and poor nation.

Being a part of a prolonged and rather complicated conflict, this full-scale war broke out after a shock-and-awe onslaught by Georgian forces on Tskhinvali, the separatist capital of South Ossetia located some five kilometres away from the de facto border. Even though the swiftness of Russia´s response has been interpreted as the corpus delicti of its evil intentions, it took a less than vigilant observer to see something was to come. Over the past months, tensions between Georgia and its breakaway regions had been rising and military confrontation had become a common sight. Immediately before August 8th, South Ossetian leadership decided to evacuate a part of its population, by itself an unprecedented step. By early August, signs of immediate escalation had become ubiquitous and Russia was certainly well informed and ready for action. The initial Georgian advance was halted and reversed after some three hours. In a nutshell, more than five years of intense and costly U.S.-led foreign military aid to Georgia produced an advance by less than twenty kilometres for a couple of hours. Afterwards, with the Georgian military effectively dissolved in thin air, the Russian troops took their time to complete what business their leadership wanted to get done. Russian forces took their time to inflict as massive a damage as they could to Georgia´s strategic infrastructure, the seaport of Poti and the only trans-Georgian railway being just examples. The next occassion for the Russians to roam about freely in Georgia might take years to come. With the fog of war dissolving, what is the impact on the energy market?

Regarding the oil transport, the Baku – Tbilisi – Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline had already been put out to a halt. Two days prior to the Georgian assault on Tskhinvali, a bomb exploded near the BTC on Turkish soil, forcing the operator to shut down oil transports for weeks. The Kurdish PKK claimed responsiblity, shifting the event out of focus. During the fighting, the BTC was also allegedly targeted by Russian jets, which the Georgian side swiftly interpreted as an attempt to destroy the facility. This isolated incident may be explained rather as a sort of message to the BTC operators, as nothing could have prevented the Russian forces from destroying the pipeline, had they intended to do so. The oil transport via the Black Sea port of Supsa has come to a halt on August 12th, the operator citing „security concerns“. Russian troops making themselves at home in the narby Poti have probably been thought to be more dangerous than the intense fighting itself, as August 12th was precisely the day on which Medvedev announced the end of Russian military actions.

The Baku – Tbilisi – Erzurum gas pipeline was working until August 12th and resumed functioning only two days later. No direct threat to the pipeline has been reported, not even by hysterical Georgian officials. Rather than the weapons used in the conflict, what we may find surprising are the ones actually not used: Russia never cut its gas supply to Georgia during the fighting, albeit it had done so several times in recent years. A possible explanation is the intention not to harm natural gas supplies to Armenia, Russia´s ally already put in a difficult position by the events.

Quite remarkably, the global oil market showed no perceivable reaction, even though the events effectively stopped Azerbaijani and Kazakh oil from using the „Georgian passage“ bypassing Russia´s pipelines. Russian troops have effectively stopped this highly valued transport routes from working for weeks, and showed a good deal of reluctance to leave central Georgia, the pipelines´ most sensitive point. Despite such tangible insecurity, the world markets recorded a decline in crude prices, actually quite a sharp one, compared to the record of several recent years. The bottom line is, there is no reason at all to claim that the energy industry in the region was caught by surprise by the events and that the war affected its business-as-usual. But are there consequences in the long run?

Not only have the Russians physically occupied territories adjacent to the highly valued and strategically important pipelines, forcing them to shut down. They even declared their firm intentions to establish a permanent presence in extensive „buffer zones“ close to South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Such a step would basically remove the advantage gained by forcing Russian troops from their cherished bases of Viazani and Akhalkalaki in recent years. What had been cited as an unacceptable threat to the BTC project in construction is escaping all attention as it is functioning.

The United States have reacted in perhaps the least self-confident way since 9/11. Strong rhetorics and high-profile visits (including the quite riduculous use of a destroyer for carrying „humanitarian aid“, instead of a freighter) are clearly less than expected by anyone, including the nervous Georgian president. The lack of a clear preference regarding the future of the region in general and of Saakashvili´s leadership in particular (accentuated by the forthcoming U.S. presidential elections) remind of Shevardnadze´s last years in office. South Ossetian war may well be the point when a replacement has to be found to overcome the barrier so painfully hit by Georgia.

In the eyes of the public, the only goal not attained by the Russians was their supposed interest in removing Saakashvili from power. A feasible explanation might be the simple remark that leaders are removed from power by being replaced by another ones and the Russians clearly had not had a full-fledged “liberation“ scenario including an alternative leadership. But, is there an option to regime change when the Russians leave? Georgian society will be left in deep depression, both economically and psychologically, with its leadership´s emblematic policies having suffered the most evident and complete defeat and foreign investors´ confidence plunging into the abyss. The opposition, once suppressed by Saakashvili´s regime, might come to pose a serious alternative.

The rhetoric confrontation accompanied by a striking lack of actions may be indicative of a change in direction. As almost anybody is more acceptable to Russia than Saakashvili, it should not be difficult to find an alternative acceptable to NATO. Such a person may also prove to be more predictable and controllable in his or her (let´s not forget several important female figures of Georgian politics) actions. The sight of a ruined and defeated important U.S. ally may lead to a number of conclusions, including the one that Saakashvili has been quite more of a maverick than fitted his role. Given Saakashvili´s deep-rooted Russophobia, almost anyone can be expected to understand the simple fact of Russian neighborhood more than he had.

As a conclusion, the recent events may well result in o certain sharing of influence in Tbilisi, or rather an acknowledgement of legitimate Russian interest in the Southerm Caucasus. Under such terms, the BTC may well lose most of its political appeal to potentially independent-minded leaders around the Caspian Sea, a signal that has probably already been understood in Astana. A partial gain of influence of Russia over the BTC means more of a loss for the others, depriving the region of the only way of exporting its oil and gas (by far largest source of income for any of its governments) without Russia´s interference. The „buffer zones“ and Russian posts along the pipelines may well be just the first steps of putting this emerging reality on the map.

August 26th, 2008

Aug 17, 2008

Reforming Slovak primary and secondary education. Or not really?

By Katka Svickova

After the summer holidays, the roughly 830 thousand Slovak pupils and secondary school students should return into a different school than the one they left at the end of June. At least this is what the new Law on Education passed by the Slovak Parliament in May 2008 envisages. And at least for a part of the pupils at first, as the law will be implemented gradually. However, what this new school will ultimately really be like, and how new it really will be, is uncertain as the real changes can only be seen in the classroom and in a few years at the earliest. In spite of this uncertainty (or perhaps facilitated by it), the reform triggered a strong critical reaction.

Main features of the Slovak educational reform

On paper, the reform goes with the freshest winds of change blowing across Europe: education should be based on new, creative approaches, explorative, project- and problem oriented methods, on own activity and participation of the pupils in their education, on new content of subjects stressing competences and capabilities rather than memorized knowledge. The number of pupils or students per class should be reduced. Schools are promised more autonomy in determining the content and the form of the subjects taught. Parents, pupils and representatives of employers´ organizations should obtain more space for direct participation in the governance of schools and in the creation of educational programs. Last but not least, the choice between schools should be free and so should be the offer of educational opportunities. So can the pupils be looking forward to an educational paradise unfolding over the next few years?

Not really, say the critics. While they agree that the educational reform is long overdue, most of them call for its further postponement – for reasons connected both to its content and to the capacity of the current system to implement it. Indeed, the reform was really fast, and there was little time for a thorough public debate: the draft was presented in September 2007, the law was passed in May 2008 and its implementation starts in September 2008. In other countries, a similar process took normally between 3 and 4 years. In the Czech Republic, for example, the educational reform, launched in September 2007, was more thoroughly debated in its preparation phase and schools got more than 2 years to get ready for it.

Given the almost astronomic speed of the reform in Slovakia, the question is how significant changes it indeed brings. And if it really signals a watershed change - breaking with the traditional centralised system oriented at pupils cramming and reproducing facts - why the scope for the discussion was deliberately so limited. Reform of the educational system turns almost all members of the society into stakeholders. One would hardly find a person today, who would doubt that education is of crucial importance for the development of the individual as well as the whole society. Yet even the short time allowed for public debate could hardly hide lack of interest from the public.

What is really in the magic box?

The critics, who raised their voice most loudly, pointed out that the new law is not a reform at all but rather a bundle of atomistic and often second-rate regulations. Moreover, its effect will be contrary to the one promised. Instdead of more autonomy, it will bring more centralization and control. Yes, individual schools should create their own educational programs. Yet according to the critics, the binding framework educational programs set by the Ministry of Education, prescribing obligatory content and conditions of education, do not give much space for schools to add their own content. As a representative of a secondary schools association said, the secondary schools will copy the ministerial framework educational programme to 95 %. And yes, the law proclaims more freedom of choice; yet at the same time, there will be always only one textbook available for free for individual subjects, approved by the Ministry. The freedom of choice of school will allegedly be limited by the power of the Ministry to set limits for the number of pupils in the individual study programs of secondary professional schools. The critics also say that the reform does not address a serious problem of inequality of chances in education. (However, besides a call for personal assistants and an improvement of the quality of elementary education, they also do not suggest any concrete proposals how to solve this complex problem). In all, despite the huge need for reform, the new law does not deviate too much from the old system.