By Michal Trnik, PERG guest author, http://michal.trnik.sk/

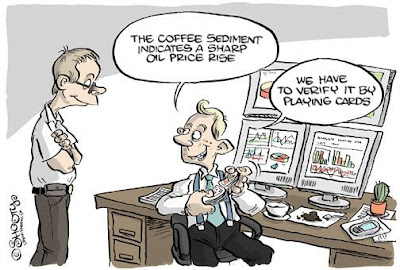

Providing credible and accurate forecasts of crude oil prices was always a tricky business resembling rather fortune telling than an exact science. With the unfolding oil price volatility, the reputation of analysts suffered a heavy blow once again. Only recently, many experts prognosticated record high $200 per barrel to be hit in a reasonably short time. Today, oil price continues its unexpected nose-dive, and oscillates below $60 a barrel, however. Source: Shooty; used and modified with the kind permission from the author.

Source: Shooty; used and modified with the kind permission from the author.

To be clear, explanations and estimates of crude prices were always a messy field. The recent unexpected price volatility unraveled weaknesses of many silver bullet explanations and left average consumers with the pressing question on their mind: "So who the hell can I blame?" The list of potential culprits has always been long.

It’s OPEC, stupid

The OPEC’s influence is still by many believed to be one of the most important causes defining the crude oil price. However, the market power of OPEC today is not what it used to be. Although the shortening of supply to increase oil price was used as a tool to boost producers’ profit, nowadays the situation is largely different as a result of OPEC being an example of undisciplined cartel; increasing availability of energy substitutes, and the nature of the current oil pricing system. The so called reference price regime in place today is based on two main freely traded reference crudes – Brent and WTI – both of which determine the price of other types of crudes, which are not freely traded. This current regime thus largely eliminates the drawbacks of the OPEC price regime (1970-85) in which prices were unilaterally determined by producers.

Crises raise prices

Political crises and instability in oil-producing regions became one of the most routine media used explanations on oil price increases. Such interpretation, however, is of no use given that political unsteadiness is rather a norm than an exception and in today’s globalized world it is fairly easy to find a geopolitical disturbance to which climbing prices can be attributed. No doubt that severe geopolitical crises can impact oil prices. Nevertheless, this explanation has to be used reasonably and with extreme caution.

Running out of oil (once again)

The Hubbert’s famous peak-oil theory rightly predicts that oil as a definite source will have to reach its production peak sooner or later. The price is expected to rise as a consequence of oil production reaching its terminal decline and thus becoming increasingly scarcer. There are many "prophets" who regularly omen that the end is near or had mistakenly announced the peak already some decades ago (video at 5:45). Briefly, we’re not there yet. Linking any oil price run-up with the alleged peak thus cannot be taken seriously.

Hedge funds, pension funds, speculators and other vermin

Various funds and fortune hunters are often accused of sky-rocketing oil prices and such view still enjoys credibility whether among consumers, politicians, analysts, industry executives, or among former chief speculators themselves.

Keeping the argument as simple as it gets, it was very recently the speculators were accused of artificial inflating of oil price, which was believed to be above the level at which demand is in balance with supply. Higher price allegedly created by artificial speculative demand would in effect mean a necessary existence of physical excess oil supply that has to be hoarded by the seller for future sale to fulfill his commitments to the buyer. Likewise, if the price is suddenly too high, then demand from the traditional consumers would shrink, leading to a large surplus of the oil in the market. The question is: what happens to this excess supply then? Well, as it is not consumed it should be stored in physical inventories somewhere. There is no empirical evidence of such accumulation at any point during the last price increase, however, which in turn means that the alleged existence of price bubble does not hold up to the economic reality.

Moreover, speculators cannot directly influence prices as they are nothing more than price bettors willing to throw their millions into the market hoping their forecasts of future price will be accurate enough to earn them profits. In any case, the oil price remains unaffected as betting on the future oil price has no direct effect on actual price moves similarly as betting on horses has no direct effect on the winner of the race no matter how much cash and how many people bet on that particular horse. It is the futures market which is the main playing field of all ‘speculators’ who instead of buying physical barrels bet on future prices of oil by buying futures contract.

What the future(s) hold

Sometimes the least sexy explanations are the most valuable ones. The futures market and trading of futures is the key to understanding the working of current oil price mechanism. The market with futures, which is a market for financial contracts, is where the oil price is determined.

The oil market, like any other commodity markets, can be divided into the spot market and futures market. In the spot market physical “wet barrels” of oil are traded. The futures market, where “paper barrels” are traded, on the other hand serves the needs of those who need oil in the future but do not want to purchase it today but rather when their actual demand arises. These traders instead of purchasing physical oil barrels opt for a futures contract which entitles them for those barrels later on. The price of such contract is set by an agreement between the buyer and seller. At the same time these contracts make predictions about the future direction of prices, which determines also the current price on the stock market. Today, only a small portion of oil is traded on the spot market, however, as it has became very thin due to its insufficient liquidity caused by a rapid decline in oil production of the two reference crudes (WTI and Brent). The futures market should not be understood as a cause of the oil price changes but rather as a place where it happens.

Current volatility and good ol’ supply and demand

In economics you won’t usually go off the track too much if you go for the supply and demand explanation whenever you are not sure about the answer. There is nothing fundamentally wrong with such answer neither in the oil markets. As the world tends to be complicated, saying supply and demand is not enough, nevertheless it is crucial for understanding the recent oil price tumble. Moreover, the recent unexpected plunge of oil price indirectly confirms that OPEC, political crises, peak oil or speculators are not the most important factors shaping the oil price.

One barrel of fresh crude without bubbles please

The recent extreme volatility is related to shocks to both supply and demand. First, the sharply increasing demand for crude in developed and developing countries combined with structurally stagnant supply stemming from persistent shortage of refining capacity stood behind the soaring price. Second, its subsequent plummet is a logical reaction to contracting demand caused by slumping economies all around the globe triggered by the credit crunch.

Supply and demand, no rocket science. Making analogies between the development of price in oil markets and the price bubble we’we encountered in the US housing market thus seems rather inadequate.

Nov 15, 2008

Crude’s Bumpy Ride: In Search of Fundamental Determinants of Oil Price

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

4 comments:

Good post. I have two questions:

1. How should we undestand seemingly much lower volatility of gas prizes?

2. Is Mr.Shooty reading PERG blog too? ;)

There is still virtually no world market with gas (LNG is still far from forming a global market) and if one adds long-term contracts, we can establish, that price of natural gas is not determined through demand and supply. Also the price doesn't really reflect costs of production - since unlike with oil, there are virtually no variable costs (beyond those of pumping and piping) of production, only comparable fixed (capital) costs of drilling, extracting and piping (which get amortized over years of operation).

Finally, the price of gas is usually based on longer-term coefficient tied to the historic prices of oil over given period - this at least partly should explain your 1st question.

Andrej offered most of the answers. Nevertheless:

1. I would be careful about making strong statements about less volatility in gas markets. It depends, as the US market this year was pretty volatile, while the European less so. This is due to the the existence of regional gas markets instead of one global as Andrej rightly points out. There is no single price for natural gas.

2. I am not completely sure if I would subscribe under Andrej's point that supply and demand does not play a role. It does, but it is more stable than in the oil's case.

3. Maybe this is a strong statement as well but gas is not that essential as oil and can be always substituted for. Moreover, it has to compete with alternative fuels.

4. Natural gas has a great "volatility potential" (rather unexplored until today)as gas supply and transport are inherently geopolitical.

5. If you are interested in more in-depth understanding of gas prices I recommend a book by Andrea Gilardoni called The World Market for Natural Gas: Implications for Europe, where you will find out that world is complicated :) and the natural gas price formation is complicated as well.

6. Answering your second question: hopefully not :D.

1. I agree with Michal's first point, you can still have domestic volatility (but the volatility tends to be rather in supply than in prices - which is partly function of long term take-or-pay contracts)

2. for this I have some reservations on the effects of supply-demand in (piped) gas.

3 Although gas is substitutable (on the long run) the effects of the short-term shortages are much more serious (if you cannot get oil for your refinery you shut down and import gas and other petrochemicals to your market from refinery that can produce (of course at market price - demand and supply kick-in). You cannot substitute gas if you are being cut-off. (Even if you were willing to pay more - unless you can import LNG). In other words I would not agree with Michal that gas is not essential (because of higher risks of short-term supply disruptions), but I agree that this conditions which he described leads to less price volatility.

4.I do not understand... Michal, you went for such a minimalistic reply in this point, that I am not sure what you mean... would you mind elaborating?

Post a Comment